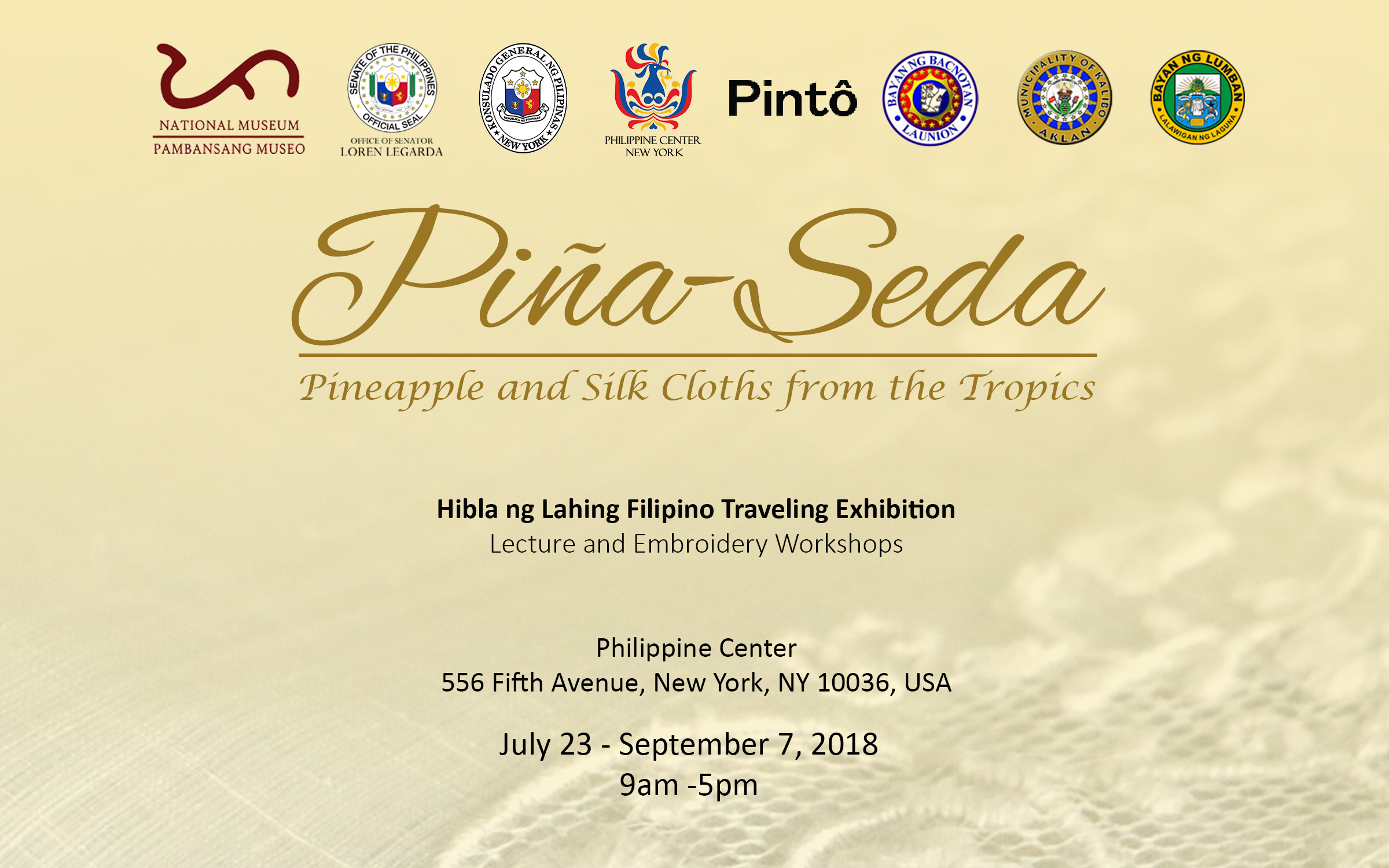

Piña-Seda: Pineapple and silk clothes from the tropics

Philippine Center Gallery

556 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10036, USA

July 23 – September 7, 2018

9am – 5pm

Piña (Spanish for pineapple) cloth is considered the finest and the queen of Philippine textiles.

Seda (Spanish for silk) cloth is undeniably the smoothest woven fabric in the world.

Piña and seda were exclusively worn and associated with the urban elite during the Spanish colonial period in the Philippines. The use of seda by the masses in the lowland was only limited to accessories such as pañuelo (large square cloth) and wrap-around over skirt as part of the traditional formal wear of woman. There were also few ethnolinguistic groups that had access to seda exemplifying its link to social status.

European travelers in the 15th century discovered piña (ananas comosus) in the American tropics. In the latter part of the 16th century, it was brought to the Philippines by the Spanish colonizers as food and was successfully grown in Panay Island as an additional fiber resource.

Seda was primarily sourced from Chinese traders through established maritime trade routes but the earliest documentation of local seda production in the country was only in the late 18th century.

Due to the scarcity of raw materials and increasing cost of piña fiber, piña-seda, a combination of piña was weft and seda was warp was developed in the early 1990s. Piña fibers have also been combined with abaca, cotton and other indigenous fibers and synthetic threads.

Piña-seda weaving

The peak of pina weaving in Kalibo was in the late 18th to the early 19th centuries, using the tanhaga (wooden foot loom) to produce pure piña cloth called Kalibo or Calivo.

There are different techniques in weaving piña-seda fibers. One technique is called pili, also known as suksuk or pechera. This is commonly used in cloth intended for barong Tagalog without embroidery. Another technique is rengue, which creates a lacework pattern similar to lace Bronson.

Knowledge on the different processes and designs has been commonly passed on from other to daughter, or grandmother to granddaughter at an early age. Children are first taught how to knot the fibers, followed by preparing the warp and weaving of plain piña cloth; design techniques are taught later.

In the past, every female member of each household knew how to process and weave pina fibers. At present, men are also engaged in weaving.

Piña-seda embroidery

Aklan woven piña cloths are traded to different parts of the country to be embellished, especially in areas known for their embroidery heritage such as Lumban in Laguna and taal in Batangas. There are also embroiders in Molo and Sta. Barbara in Iloilo, Bocaue and Santa Maria in Bulacan, and Malabon and Paranaque in Metro Manila. these are decorated with flat, raised or relief embroideries such as flowers, fruits, vines, tendrils, leaves, butterflies, and geometric designs.

The designs and patterns are initially of Spanish, French, Belgian, Iranian, and Chinese origins that were later combined with indigenous plants and animal motifs. These were handed down from one generation to next with mior alterations and local terms describing each design may vary from place to place.

The embroidery of piña-seda cloth involves a number of individuals and stages. The woven cloth is first brought to the designer where the actual size of the design is drawn, traced or stamped on the cloth. This is passed on to the embroiderer wherein preliminary stitches are made using cotton threads to give an embossed effect while calado is done next to highlight the embroidered parts.

Each embroiderer of piña-seda cloth involves a number of individuals and stages. The woven cloth is first brought to the designer where the actual size of the design is drawn, traced or stamped on the cloth. This is passed on to the embroiderer wherein preliminary stitches are made using cotton threads to give an embossed effect while calado is done next to highlight the embroidered parts.

Each embroiderer has a specialization, which may be tapado (embossed), sombrado (shadow applique), “ethnic” (free-form motif), or calado (open-work). The most coveted skills are sombrado and calado.

The embroidered cloth is hand washed using tap water and mild detergent to remove any traces of dye and other stains. Then, it is stretched and applied with aimirol (starch paste) before sun-or air-drying.